A Skillful Facsimile Page in a 1611 King James Bible

There’s an intriguing tradition of a “crocodile mystery” on the Folger Shakespeare Library blog, “The Collation,” which periodically posts the mystery in question, awaits comment, and then posts an explanation a few days later. Earlier in May, we were intrigued by a crocodile mystery image that looked like a page from the 1611 King James Bible. What was so mysterious about this image? Was something not as it appeared? The answer, from Collation author Sarah Werner, Undergraduate Program Director at the Folger, concerned a fascinating nineteenth-century phenomenon, the “pen facsimile.” We wanted to share the following excerpt from her Collation blog post, which you can read in full here:

———————————–

As the commenters on our May 3 crocodile guessed, the mystery image shown there, and repeated here, shows writing masquerading as print or, to use the more formal term, a pen facsimile. (Click on any image in this post to enlarge it).

The book in question is the Folger copy of the 1611 Authorized Version of the Bible, also called the King James Bible. The last leaves of the book are increasingly damaged—the corners are missing and repaired with blank paper—until the final original leaf is entirely gone. In its place is a pen facsimile, a hand-drawn copy of what the original leaf would have looked like.

As you can see by comparing the facsimile with the original leaf, shown here from a copy at the University of Pennsylvania, the facsimilist did a very good job. But you can also see, when you’re looking for it, that the pen facsimile is just a bit wobblier than the print original. The kerning (the adjustment of spacing between letters) is just slightly irregular; some long-s’s are missing their crossbar; and the three capital-G’s starting the instances of “God” in the third verse are all just slightly differently shaped.

Once you know which is which, it’s hard to “unsee” the details that reveal it as a facsimile.

At left: Pen facsimile of final page from Folger copy. At right: original printed page from 1611 King James Bible, University of Pennsylvania

Adding pen facsimiles of missing or damaged leaves was not unusual in the nineteenth century for collectors who preferred their works to be pristine and perfect, a common preference. Adding such a facsimile was referred to as a way of perfecting the copy. The verb “to perfect” is one of those odd bibliographical terms that shows how much standards and tastes have changed since we’ve been studying rare books and similar objects. To perfect a book was to supply any missing or damaged leaves with leaves from another copy of that book or with facsimiles of those leaves. By our modern-day standards, of course, this is far from a perfect practice and one that libraries today don’t follow.

It’s not clear who the facsimilist was for the Folger’s King James Bible, or when the work was done. There’s a note in the catalog of the former owner, W.T. Smedley, from nineteenth-century Bible expert Francis Fry, attesting to the book’s good condition and noting that “The last leaf is repaired. It is very rare. They are so often lost.” Either Fry was using “repaired” as a euphemism for “facsimile” (although this seems unlikely, since he accurately describes the volume’s title page as a facsimile) or it was done after Fry examined the book.

Facsimilists, including the unknown figure who created the final page of the Folger’s KJV, were not intending to deceive anyone by passing off copies as originals. Rather, the intent was to make as close to complete as possible copies of works that were missing leaves. While I’m astounded by the talent of such a facsimilist as we just saw, my favorite pen facsimile, shown here, reveals not remarkable skill, but remarkable desire. This title page is from one of the 82 copies of the 1623 First Folio of Shakespeare in the Folger collection. It’s not what I would do if I owned a First Folio with a torn title page, but then again, I can’t begrudge the desire of this long-ago owner to make clear what this book is.

Sarah Werner is the Undergraduate Program Director at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

To read the rest of this article, including additional amazing images of pen facsimiles and their print equivalents, read the full blog post on The Collation. For more information about another facsimilist, John Harris, and a bibliography of books and articles related to the practice, consult this interesting page from the British Library.

To explore more of the Folger first edition of the 1611 King James Bible, complemented by notes and read-aloud audio, consult our online feature Read the Book. Since the Folger copy lacks an original title page, as co-curator Steve Galbraith explains in his title-page audio comment, Read the Book uses the original 1611 title page from a Bodleian Library copy.

May 16, 2013 | Categories: The KJB in History | Tags: Authorized Version, facsimile, First Folio, history of the book, King James Bible, manuscripts, pen facsimile, rare books, Shakespeare, The Collation | Leave a comment

Myths Debunked: King James and the King James Bible

OK, more myths to bust. King James I did not translate the King James Bible, and he was also no saint! I’ve seen at least one recent book (a collection of KJV excerpts) entitled King James’s Bible. The implicit claim of this title is true, to the extent that the KJV was commissioned by King James, and it was presumably the Bible he himself used from 1611 until his death in 1625. But, in this last sense, it was pretty much everybody else’s Bible, too.

James certainly did not do any of the translating of the KJV. He was a very scholarly king, interested in theology and the Bible. Among other works, he wrote a book on demonology (1597) and a learned exposition on several chapters of Revelation. He also translated some of the Psalms into meter, but this practice tended to involve turning English prose versions into verse, rather than rendering the original Hebrew into English. Lots of people wrote metrical Psalms at this period, and most didn’t know Hebrew.

James set the KJV ball rolling, but once it was in motion he more or less left it alone. The eminent scholars worked away on the project for years, without any involvement from the monarch. The dedicatory Epistle to King James at the front of the KJV refers to the king as the “principle mover and author of this work.” However, the word “author” in this case doesn’t mean what it does in a phrase like “the author of Shakespeare’s works is William Shakespeare.” It’s closer to our word “authority,” or really someone who authorizes or instigates (as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it).

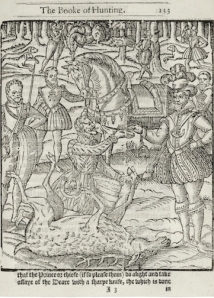

James I at the hunt (standing, right). Gascoigne, The noble art of venerie or hunting. 1611. Folger.

It’s interesting that the British tend to refer to the KJV as the “Authorized Version,” while Americans prefer the “King James Bible.” The term “Authorized Version” dates from only the nineteenth century, while as early as 1723, according to one writer, it was “commonly called King James’s Bible.” In the seventeenth century, most people just referred to it as the new or latest translation. For the first American edition of the KJV, the “Revolutionary Bible” of 1782, the printer Robert Aitken carefully removed any reference to King James.

I’ve also occasionally heard the KJV described as the “St. James Bible.” Maybe people have the “St. James Infirmary Blues” going through their heads, or they’re thinking of the many churches dedicated to St. James (there are actually several saints by this name, including St. James the Great, St. James the Less, and St. James the Just). I don’t know. But the only James associated with the KJV is King James I, and he was never canonized. Not only was he less than saintly in his behavior (a bit of a party animal), but he was not a Catholic, which seems a fairly basic requirement for sainthood.

We can keep calling it the King James Bible, but we shouldn’t let that nickname mislead us into giving James more credit than he’s due.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library, on view through January 16, 2012.

December 28, 2011 | Categories: From the Curators, The KJB in History | Tags: Authorized Version, demonology, King James Bible, King James I, Psalms | 1 Comment