The Manifold Greatness blog is no longer active, but remains available here as an online archive to explore. For more information about the King James Bible, its history and influences, consult the Manifold Greatness website, http://www.manifoldgreatness.org.

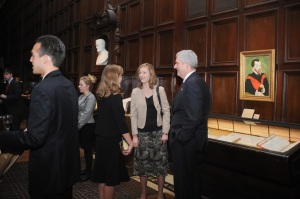

2011: Representative Daniel Webster of Florida previews the Folger Manifold Greatness exhibition. R. David / National Endowment for the Humanities.

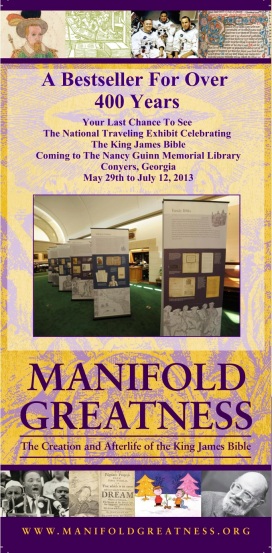

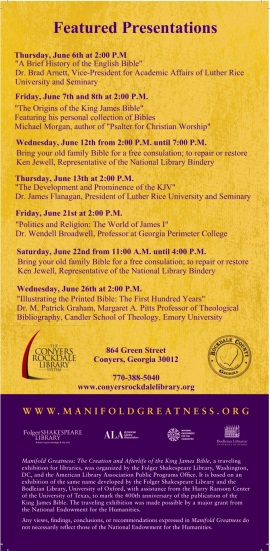

Today is Friday, July 12, 2013, the last day for the touring exhibit of Manifold Greatness: The Creation and Afterlife of the King James Bible, which has traveled to 40 libraries across the United States. The original Bodleian Library and Folger Shakespeare Library exhibitions of 2011 are long over, as is the 2012 Ransom Center exhibition. We’ve shared some final words in recent posts from the curators of the Folger exhibition, Steve Galbraith and Hannibal Hamlin, who have written on this blog many times. And so, with the conclusion of the touring exhibit, it is time to end the Manifold Greatness blog as well.

Starting in March 2011, this blog has debunked myths about the King James Bible; explored KJB-related anniversaries and holidays; offered a guide to family and young visitors’ activities; examined American historical milestones from Jamestown and the Mayflower to the speeches of Martin Luther King; taken close looks at many rare and historic materials from the exhibition (including a Civil War prisoner’s Bible and one owned by King James’s son, Prince Henry), and highlighted the cultural influences of the King James Bible, ranging from A Charlie Brown Christmas and the lyrics of Bob Marley to Handel’s Messiah and William Blake. (Late in 2011, swept up in year-end listmania, we also gathered our “top 10 posts,” including a King James Bible owned by Elvis Presley.)

We’ve reported often, too, on Manifold Greatness events, from the traveling panels’ debut, to numerous events and displays at the traveling exhibit host sites, to lectures, exhibition openings, and other occasions, including the NEH exhibition preview for members of Congress pictured above. See this blog post on the congressional reception for more photos—and the story of the 1782 Aitken Bible, the only Bible ever recommended by Congress.

In the words of Ecclesiastes in the Byrds’ #1 hit in 1965, “Turn, Turn, Turn,” however, “To everything there is a season.” And while the King James Bible translators—and the Byrds—surely did not have blogs in mind, the same insight still applies. With the conclusion of the traveling exhibit, it is the “season” for this blog to finish, too. We thank you for your encouragement, participation, and support during its run of almost two and a half years. We also offer special thanks to everyone who has written for the blog, all of whom we’ve listed in the Sponsors and Credits page.

For more information on the King James Bible of 1611, including its origins, creation, and later influences,we encourage you to explore the extensive, rich content of the Manifold Greatness website.