Just for Kids (and Families): Berry Ink, Online Printing, and More

The King James Bible has inspired plenty of children’s and family activities as part of the Manifold Greatness project. One of the most popular original videos on our YouTube channel is Making Ink. There’s a sequel to that one, Making a Quill Pen, another video on Making a Quarto, and still another on Making a Ruff—the essential fashion statement for a well-dressed King James Bible translator!

And there’s more: on our Manifold Greatness website, all four craft videos come with suggested supplies and other tips. (There’s a printing demonstration video by Manifold Greatness co-curator Steven Galbraith, too.) The website’s Kids Zone also includes All About the King James Bible, which is filled with cool facts and image galleries, a family guide, and many online activities.

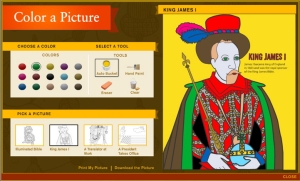

Among the online games and activities, you’ll see some of our favorite features, including a “translator scavenger hunt” that helps you search for a translator’s ink, pen, glasses, and more, an audio-rich translation comparison, an online printing press, the chance to design your own book bindings, crossword puzzles, and highly original pictures to color.

For more materials on the subject, you may wish to explore our past blog posts on Ideas for Educators (from Teacher Appreciation Week in 2011) and The KJB and Young Audiences, as well as this report from Tifton, Georgia, on a Making a Quarto workshop during the Tifton exhibit of Manifold Greatness. (For more on a family classic influenced by the King James Bible, by the way, read Manifold Greatness co-curator Hannibal Hamlin’s post on My Favorite Exhibition Item?, including his thoughts on A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965).)

Manifold Greatness: The Creation and Afterlife of the King James Bible, is on view at Nancy Guinn Memorial Library in Conyers, Georgia, through July 12, 2013. For a wealth of material on earlier English Bibles, the origins and translation of the King James Bible, its diverse early formats, and its widespread cultural, literary, and social influence for the next 400 years, see our website, www.manifoldgreatness.org.

Translating Manifold Greatness from Scholarship to Exhibition

Miles Smith, one of the King James Bible translators. (c) The Governing Body of Christ Church, Oxford.

Back in 2009, when we first started working on Manifold Greatness, we identified a number of themes we wanted the exhibition to touch on, and one of those was the nature of translation. In our grant proposal, we talk about how translation is a true literary act, one that requires choices in tone, style, vocabulary, and emphasis, and how translation is a process of culture adapting, changing, and potentially growing. On our main website, we note that the translation of the KJB was, above all, a collaboration.

The Manifold Greatness traveling panel show is now on the way to its final location, the Conyers-Rockdale Library System in Conyers, Georgia, where it will appear, with much related programming, from May 29 to July 12. And as this touring phase comes to a close, I’ve been looking back at our own process, and thinking about the way in which exhibitions themselves are a process of translation. Of course we collaborate—anyone who has worked on an exhibition can tell you that it is one of the most collaborative undertakings they have experienced. But because we tend to think of translation as a text moving from one language into another, it’s not immediately obvious that the work we do in exhibition is also a process of translation. And yet, on many levels, I think it is.

We begin with an idea, and shape it into a narrative: here is our story; here is what can be said about the history of the King James Bible. But as scholars, our curators have a certain language, a way of packaging their knowledge. This does not always (ahem) translate well to an audience which may be made up of everyone from schoolchildren and educators to tourists or subject specialists. We need a way of speaking, and of writing, that provides information accurately and succinctly, and in accessible nuggets for a broad range of audiences.

For Manifold Greatness, we did this twice: once for the artifact-based exhibition in Washington, DC, and again for the panel exhibition that traveled the country. For these, we needed two different “languages.” The Washington, DC, show was in the language of artifacts, showing the here and now, and revealing KJB stories through what could be seen on the open pages before a visitor. The traveling show retracted the lens a little further, and gave weight to story over object. We covered the same material, but we translated the content in slightly different ways in order to best serve the format of the shows.

I like to think that the KJB translators would have appreciated our process. Our translation process was, like theirs, concerned first and foremost with accuracy. Every word needed to be true; each idea needed to be formed and informative. We were not reading Hebrew, Greek, and Latin—but remember, of course, that the King James Bible was not the first English Bible, and the translators drew liberally from the English translations that came before. Although they produced a masterpiece of English literature, their concern was not for lyricism or rhetorical power; they aimed for accuracy as they translated both from ancient languages and from previous English versions.

Have a look at the website to compare translations, and see for yourself how the KJB translators ended up creating a new version at once lyrical and accurate. One of my favorites is the passage from Ecclesiastes (1:2), in which the translators don’t really change the meaning or emphasis from the previous English translation, but they manage to create a verse that is poetic, song-like, and memorable—and also just that much more true to the original Hebrew:

Great Bible (1539)

All is but vanity (saith the Preacher) all is but plain vanity.

King James Bible (1611)

Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity.

Would that our exhibit text was as memorable as that! Perhaps it is indeed vanity to compare our process to that of the King James Bible translators. But as we near the end of this commemorative exhibition, I’m very pleased to have been part of such a process, to understand it, and to see the many thousands of people we have reached through the work that we did to turn ideas into language, and to use language to deliver the right information.

Caryn Lazzuri is the Exhibitions Manager at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The Translator’s Dilemma, or How DO You Say That in English?

The Manifold Greatness exhibit provides a great deal of information about how the King James Bible came into being. We are told that the translators were instructed to work from the wording used by the Bishops’ Bible (1568), unless the wording used in the Coverdale or Geneva Bibles, for example, was judged to be closer to what the older Greek and Hebrew texts intended. It seems at first as though it would be easy enough to determine which translation was more accurate and arrive at a Bible that ticked all the boxes for the various interested parties.

On Thursday, May 2, Pastor Earl Steffens, pastor of Peace Lutheran Church, gave a presentation he called The Translator’s Dilemma or How DO you say that in English? The lecture outlined the problems that Biblical translators through the ages have had when attempting to either make a new translation of a Bible from “original” sources, or to translate a Bible from one language to another.

Plantin Polyglot Bible (includes Hebrew, Greek, Syriac, Aramaic, and Latin), 1568-1572. Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

What is the most basic problem for people attempting a new translation? Having to decide which documents to use as a basis for that translation. Which of the texts in Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Latin are the closest to what the original authors actually wrote? The primary documents, called autographs, are long gone. All that is left are copies. And copies of copies. And copies, of copies, of copies. Needless to say, there are plenty of discrepancies between various copies of the scriptures that have come down to us. A good translator looks at all the variations on the text and decides what is the most likely original wording and meaning—in an ideal world, without tinting that decision with political or theological agendas.

The second problem for a translator is “How DO I say that in …”—how to convey, as closely as possible, what the original author of the text intended. Word for word translations are stilted and awkward. Pastor Steffens used the example of the three words that Greek authors use for three completely different kinds of love and how, in order for English speakers to understand the difference between them, translators use phrases to clarify the meaning. And, of course, translators want the result to sound good, to convey the correct meaning, and to be relevant to the intended audience. Translation is more of an art than a science.

The audience asked some great questions.There was some discussion of how oral tradition might have impacted translation—it seems quite possible that, if you had heard a Bible story one way all your life, you might add bits of the story as you know it to your copy of the text as you sat in the scriptorium scribbling away. There was also some discussion of the merits of various English translations, with the King James Bible being the hands-down favorite of a number of the participants.

Vickie Horst is the Manager of Tifton-Tift County Public Library in Tifton, Georgia.

To learn more about the Plantin Polygot Bible shown above, consult the Early Bibles image gallery; you can learn more about George Abbot (above) and other King James Bible translators in our Meet the Translators online feature.

Opening Manifold Greatness with Theatrical Flair

The Manifold Greatness exhibition officially opened at Harford Community College (Bel Air, Maryland) on April 22, 2013, with a reception, a lecture, and theatrical readings.

Associate Professor of Philosophy and Religion Gary Owens lectured on “Catholicism, Protestantism, Blood, Guts, Ink and the King James Bible” to a room filled with community members, students, and faculty. Nearly every seat was taken.

In his lecture, Dr. Owens described in depth some of the earlier efforts to translate the Bible into English (and into other languages than Latin), as well as placing the work of translation in context and explaining the risks—and in many cases, the consequences—of this work. The bountiful and compelling slides that illustrated his narrative, as well as his lively presentation style, brought this history to life for all participants. The audience stayed well past the planned 75-minute lecture and discussion to ask questions and learn more about this history.

The reception was scheduled from 3 to 7 p.m. and attracted many viewers over the course of four hours. During the last hour of the reception, HCC Associate Professor of Theater Ben Fisler spoke about the explosion in the development of the English language that was taking place at the time that Shakespeare wrote and during the period of the translation of the King James Bible.

Two HCC students performed monologues from Much Ado About Nothing and Twelfth Night, and Mike Brown (in the person of the great Shakespearean actor, Junius Brutus Booth) gave a dramatic reading of Psalm 46 from the King James Bible.

The Booth family home, Tudor Hall, is located just a couple of miles from the college, and Tudor Hall is a partner in HCC’s presentation of Manifold Greatness.

A more extended version of the readings and talk is scheduled for May 9 from 6 to 9 p.m., under the title ‘A Great Feast of Languages’: The Language of Shakespeare and of the King James Bible.

Carol Allen is the Library Director of Harford Community College in Bel Air, Maryland.