Looking Back, and Far Ahead

I’m writing this from Borough High St. in Southwark (London), a few blocks from Southwark Cathedral, and in the vicinity of what used to be Winchester Palace, the London residence of the Bishop of Winchester. Lancelot Andrewes, translator of the King James Bible and perhaps supervisor of the First Westminster Company, was granted the bishopric in 1618. He is buried in Southwark Cathedral and is represented in effigy lying on top of his tomb.

London is full of reminders of the translation of the English Bible. Across London Bridge, which is just up the road and on the right, is the church of St. Magnus Martyr. Miles Coverdale, who translated the first complete English Bible (apart from the Wycliffites), is buried there, since he served for a time as rector.

William Tyndale, translator of translators, is buried in Vilvoorde in the Netherlands, where he was strangled and burned, but his sculpted head is included as a decorative architectural feature at St. Dunstan-in-the-West, where he lectured. John Donne later preached at St. Dunstan’s. A little south of St. Paul’s, where Donne was dean, stood the church of Holy Trinity the Less, destroyed in the Great Fire. John Rogers, the man responsible for Matthew’s Bible (1537), was rector there a few years earlier. He was later burned alive as a heretic at Smithfield, a 10 minute walk north, near the church of St. Bartholomew the Great. Benjamin Franklin worked briefly for a printer in the Lady Chapel of St. Bart’s.

Of course, Westminster itself, the location of two companies of the King James Bible translators, is down the Thames to the west. Thomas Bilson, Bishop of Winchester (before Andrewes), member of the Second Cambridge Company, and one of the revisers of the final King James Bible text, is buried in Westminster Abbey, as is, of course, King James I. Archbishop Matthew Parker, who supervised the translation of the Bishops’ Bible (1568), is buried at Lambeth just across the Thames.

The celebrations of the King James Bible anniversary have died down here. There are no upcoming events listed on the website of the King James Bible Trust. And in the United States, the tour of Manifold Greatness comes to end on July 12—oddly enough, my birthday. Perhaps more appropriately, it is the date of the death of Erasmus (1536), who produced the Greek text of the New Testament that became known as the Textus Receptus, an essential resource for translators from William Tyndale to the King James Bible companies.

As I reflect on the long history of Manifold Greatness, from its inception and planning, to the years of research, to the exhibition at the Folger, to the long journey of the panel exhibitions, I wonder what lies ahead for the King James Bible in 2111. Will the 500th anniversary be celebrated as were the 400th and the 300th? Will the King James Bible still be in use in some churches? Will American presidents still be sworn in on it? Will the King James Bible have an afterlife in the 21st century? Will some lecturer refer back to the 2011 anniversary celebrations at the Folger, as I referred in my opening lecture to celebrations in New York and London in 1911? Few of us will know. As Matthew writes, “of that day and that hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father.”

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, was co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Walt Whitman’s American Bible

Happy Birthday, Walter! Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass is deeply indebted to the King James Bible, despite Whitman’s claims to be utterly original. In fact, Whitman wrote of his work as “the Great Construction of a New Bible.” The first, slim, volume of Leaves of Grass was published in 1855. Whitman paid for it himself, and there were fewer than 800 copies. The rest of Whitman’s poetic life was spent revising and adding to this collection, culminating in the final “Deathbed” edition of 1891. The original 95 pages had swollen to almost 450, and the 12 poems of the 1855 edition had become nearly 400.

Various explanations have been offered for Whitman’s title, “Leaves of Grass,” including the obvious pun on the “leaves” of a book. But somewhere in the background is probably the statement of Isaiah that “All flesh is grass, and all the goodliness thereof is as the flower of the field: The grass withereth, the flower fadeth: because the spirit of the LORD bloweth upon it: surely the people is grass” (Isaiah 40:6-7). Isaiah’s grim prophecy of death is transformed by Whitman into a celebration of the natural cycle, in which death is part of life and the poet, like all the people he sings of in his poem, returns to the earth from which he came. As Whitman writes in “Song of Myself,” “I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love,/ If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles.”

“Song of Myself,” the first poem in the 1855 edition, may also derive its title from the Bible. The great Old Testament celebration of love is the Song of Songs or Song of Solomon, an erotic dialogue between a man and a woman rich in metaphors of spices, fruits, animals, and birds. Whatever the original author intended, Jews and Christians have both traditionally interpreted the poem as an allegory for the love between God and humanity. Whitman’s “Song,” typically and radically, is not of God, or even a lover, but of himself: “I celebrate myself, and sing myself.”

One striking feature of Whitman’s poetry is his rambling but rhetorically powerful prose-poetic line, often full of lists of people, places, and things. He adapts this line, just as William Blake did before him (and Alan Ginsberg after), from the parallelistic prose of Isaiah and other Old Testament prophets, in the King James Version. Leaves of Grass may be a new American Bible, but in some ways it sounds a lot like the old one.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, was co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Note: You can read (or hear) about the Whitman engraving shown here on the web page Personalizing Shakespeare, by Louis B. Thalheimer Head of Reference Georgianna Ziegler.

Casiodoro de Reina and the Bear Bible

Yesterday was March 15, the anniversary of the death of Casiodoro de Reina (ca. 1520–1594). And that made us think of the Bear Bible, or Biblia del Oso, first published in 1569. The translation was largely the work of de Reina, a Spanish Reformer who began his religious life as a monk in the monastery of San Isidoro outside of Seville.

Persuaded by the writings of Martin Luther, de Reina fled Spain when he aroused the suspicions of the Inquisition. After a brief stay in Geneva, which he found uncongenial, de Reina traveled to England. In 1559 he became the pastor of the Spanish Protestant exile community in London, who worshipped at the church of St. Mary Axe, named after a neighboring tavern whose sign bore the image of an axe.

Seemingly trumped up due to the machinations of Spanish agents, accusations against de Reina included an astonishing array of crimes, among them dishonesty, embezzlement, immoral conduct with female congregants, and sodomy, as well as doctrinal and ecclesiastical errors. He fled England with his family in 1563 and devoted himself to the translation of the Bible, as well as to writings criticizing the Inquisition.

There had been earlier Bibles in Spanish, but de Reina’s, first printed in Basel, was the most influential. The de Reina Bible was revised in 1602 by Cipriano de Valera, originally a member of the same monastic order as de Reina, who was, from 1559, a professor at the University of Cambridge.

Though it was revised again several times up to the twentieth century, this Spanish Protestant translation is still known, and still in use, as the Reina-Valera Bible. It has a status among Spanish Protestants somewhat equivalent to that of the King James Bible among English speakers. The charming printer’s mark of the bear climbing a tree for honey identifies the work of the Bern printer Mattias Apiarius, whose name (in his native German, “Biener”) means “beekeeper.”

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, was co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Looking Back

Rockwell Kent. Plattsburgh State Art Museum. Bequest of Sally Kent Gorton. Copyright 1930, R.R. Connelley & Sons, Inc and the Plattsburgh College Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved.

Well, as I write this, Manifold Greatness is coming down, making way in the Folger’s Great Hall for the next exhibition. I’m in Columbus, but I can imagine the Bibles and books being carefully carried back down to their usual resting places in the Folger vaults. The couriers are sealing up loan items to transport them back to their homes at the Library of Congress, the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, Graceland (Elvis Presley Enterprises, Inc.), the Bodleian Library, Lambeth Palace, and elsewhere. The Hamlin Family Bible will find its way back to me. The ever-resourceful Caryn Lazzuri will no doubt find a storage space for the antique radio she scrounged up for the exhibition, and the pulpit and pew we borrowed from the Lutheran Church of the Reformation will be returned.

It’s been a remarkable experience planning, making, mounting, and writing and talking about Manifold Greatness. Thinking back on how much it involved is almost dizzying. And I’ve learned so much. I remember coming (online) upon the John Alden Bible at Pilgrim Hall, for instance, and how exciting it was to think that this might have been the first King James Bible in America. We almost got a Bible owned by Bob Marley, a photo of which we did use on the traveling panel exhibition. That loan, like some others, didn’t work out, but Elvis’s King James Bible was a fine addition. It was fun to see this loan, and Manifold Greatness, advertised at Graceland, which I visited in November. We borrowed Bibles and other books from around the world; the Library of Congress and the Bodleian were especially generous. Steve Galbraith, Caryn, and I sat down with Mark Dimunation, the Library of Congress’s Chief of Rare Books and Special Collections, and he showed us some gems: the Massachusett Bible of John Eliot, the first Bible printed in America, and Robert Aitken’s “Revolutionary” Bible, America’s first homegrown KJV. We made a pitch for the KJV Abraham Lincoln was sworn in on, but it had been traveling too much and needed a rest from exhibitions. A happy alternative was the George Washington Family Bible, which we found at the George Washington National Masonic Memorial, across the Potomac in Alexandria, Virginia.

John Bois’ manuscript notes of the proceedings. Courtesy of Corpus Cristi College, University of Oxford.

Especially momentous was the loan of the “Big Three,” the only surviving manuscripts from the KJV process itself. Manifold Greatness brought these together for the first time; they’re normally at the Bodleian Library, Corpus Christi (Oxford), and Lambeth Palace (London). They met first in Oxford’s exhibition and then travelled to the Folger, their first visit to America as well. I was fascinated, as visitors were, by the Bishops’ Bible with the inscriptions of one of the KJV translators, deleting a word here, adding one there, noting changes in the margin. I gave at least half a dozen tours of the exhibition, and it was a treat to be able to read aloud from this document, showing how the specific language of this most influential of books actually came into being.

My memories stay with me, but I’ll miss the physical experience of the exhibition. I loved the contrast between the massive and luxurious Bishops’ Bible of Queen Elizabeth I and the tiny, spare Bible brought to sea by Justinian Isham. The case of Literary Influences (also viewable as an interactive timeline on the exhibition website) was another favorite. I hadn’t realized until they were all in place what a radical bunch of biblical writers we’d assembled: John Milton, John Bunyan, William Blake, Herman Melville, Allan Ginsberg. You could practically hear their rebellious roaring through the glass! Finally, being able to walk from the case with the fragile little leaves from Tyndale’s 1530 Pentateuch across to the 1968 photo of Earthrise, listening on cellphone to the Apollo 8 astronauts reading Genesis from outer space—that was an amazing leap across the centuries. Manifold Greatness indeed.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, was co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The Hamlin Family Bible

It was a particular treat to be able to include a Bible from my own family in the Family Bibles case of the Folger Manifold Greatness exhibition. My fellow exhibition curator Steve Galbraith, exhibition manager Caryn Lazzuri, and I had been looking for a nineteenth-century Bible to represent the later history of family Bibles, when publishers provided pre-printed genealogical pages. We also thought it would be good to use an American Bible, continuing our transatlantic story.

Around the same time, after my father’s death in January 2011, I came across an old Bible in my parents’ home in New Haven. It was an old, somewhat worse-for-wear, King James Bible, printed in Boston in 1841 by B.B. Mussey. A battered plastic wrapper around it still had a mailing label attached, addressed to Louise Hamlin, known to me in childhood as “Cousin Louise.” On looking through the Bible, I found some family history recorded on blank leaves between the Old Testament and the New, one of the places often used for this purpose. The information related to, and was presumably written by, my great-great-great grandfather, Hannibal Hamlin.

Hannibal Hamlin is actually of more than family interest, since he served as Vice-President of the United States from 1861 to 1865, during the first term of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency. Hamlin entered politics in his home state of Maine, where he was a member of the House of Representatives. Hamlin later served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, and Governor of Maine, before becoming Vice President. He started out as a Democrat, but in a move that caused considerable shock in Washington, he crossed the floor of the Senate in 1856 to join the new Republican Party as a protest against the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Hamlin was a life-long opponent of slavery, which was part of the reason he was dropped from the ticket for Lincoln’s second presidential campaign.

In the Bible, Hamlin records his two marriages, first to Sarah Jane Emery. Sarah Jane died in 1855; Hamlin must have liked the family, since he married her sister Ellen Vesta Emery the next year. The births of Hamlin’s children are also recorded in the Bible. Charles and Cyrus were the most important historically, both serving as officers during the Civil War. Cyrus championed the enlistment of African-American troops, and led a brigade of black soldiers at the Siege of Port Hudson. On retirement he was awarded the honorary rank of brevet major general. He died of yellow fever in 1867. Charles fought at Gettsyburg, and retired with the honorary rank of brevet brigadier general. Charles and his sister, Sarah, were at Ford’s Theater the night Lincoln was shot.

Charles had a number of children. One of them, Cyrus, was my great-grandfather. Another, Charles Eugene, was the father of Louise, to whom the Family Bible was passed down, along with much other family memorabilia. I still have Hamlin’s baby rattle, the walking sticks that got him around Washington, his copy of Byron’s works, and lots of pictures. Charles Eugene also wrote a biography of the vice president. I’m lucky to have so much information about my family history, but like so many American and British families, I have some of that information stored in the old family Bible.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Shakespeare and the King James Bible: Ships Passing in the Night

Since at least the great Shakespeare Jubilee of 1769, Shakespeare and the King James Bible have been yoked together as the twin pillars of English culture. Dozens of books in the nineteenth century printed extracts from Shakespeare and the KJV, often on facing pages, showing that they were morally and spiritually equivalent on matters such as the Sabbath, the World’s Dissolution, Fears, Adultery, and Wisdom.

The association of these two works (and neither of them really is “a work”—they’re both anthologies) encouraged the idea that there must be a stronger link between them. I’ve written before about the nutty notion that Shakespeare was a KJV translator. But even the idea that Shakespeare read and was influenced by the KJV is mistaken.

Shakespeare did read the Bible, and he heard it in church. We can tell this because of the hundreds of biblical allusions and references in his plays and poems. In fact, there is no work that Shakespeare alludes to more often than the Bible. Bottom garbles Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (“The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen…”); Richard II compares his tormentors to Judas and the Pharisees; Shylock cites the story of Jacob and Laban from Genesis; King Lear alludes (unconsciously) to the Book of Job. Shakespeare makes these allusions, counting on his audience to recognize and interpret them, and so add deeper meaning to the play.

The KJV was published only in 1611 (possibly even in early 1612, since England was still on the old calendar with New Year’s in March), and while parishes in London and some other dioceses did acquire copies of the new Bible fairly quickly, it was not immediate. Up until this time, Shakespeare, like everyone else, had known other English Bible translations. The Bishops’ Bible (first published in 1568) was the official translation read in most English churches. The Geneva Bible (1560) was by far the most popular, though, and Shakespeare obviously had a copy that he read from, since most of the biblical allusions in his works that are identifiable with a specific translation are to the Geneva.

The KJV simply arrived too late for Shakespeare to know it. Even if he did see a copy or hear it in church, it didn’t supplant the Geneva from his ear and memory. Moreover, by this time Shakespeare had only a few more plays to write before he died: perhaps only the Fletcher collaborations, Henry VIII, Two Noble Kinsmen, and the lost Cardenio. It’s probably unreasonable to put too much emphasis on one Bible translation or another, however, since most of the translators (KJV companies included) saw themselves as revisers, and the succession of translations from Tyndale and Coverdale on as just stages in the development of the English Bible. Shakespeare knew the English Bible intimately—just not in the revision known as the KJV.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The First King James Bible in America?

As we approach Thanksgiving, perhaps thinking of those Pilgrims who came over on the Mayflower and feasted with the Indians, we might think about the English Bibles they brought with them. (We ought to note, though, that despite the popular myth about the Pilgrims founding Thanksgiving, it was actually Abraham Lincoln who fixed the official November date after the Civil War. The Pilgrims had a feast of “thanksgiving” in 1621, but it was hardly the state holiday we know today.)

As the hotter, more godly variety of Protestants, the Pilgrims used the Geneva Bible. It was far the most popular English Bible until the mid-seventeenth century, but especially so among those termed Puritans, given its associations with Calvinist Geneva. John Alden, however, brought a copy of the King James Bible printed in 1620. Though Alden became a prominent member of the Plymouth Colony, he wasn’t originally a member of the Pilgrims, but rather the ship’s carpenter on the Mayflower. This may explain why he carried the KJV.

Alden’s 1620 KJV may be the first copy of this translation on American soil, but it’s impossible to be certain. The Roanoke Colony was settled long before the KJV and the colonists had disappeared by 1590. Jamestown was founded in 1607, again too early for the KJV. The first colonists probably brought Geneva or Bishops’ Bibles.

The question is, were copies of the KJV brought to Jamestown between its first printing in 1611 and the arrival of the Mayflower in 1620? Alden Vaughan, professor emeritus at Columbia University, informs me that there was considerable traffic across the Atlantic in those years, and it might yet be possible to determine whether Bibles were part of the cargo.

On the other hand, as Kenneth Fincham pointed out at the Folger Institute conference in September, English churches did not immediately purchase that KJV when it was hot off the presses. Within a few years most London churches acquired copies, but in other dioceses churches were using the Bishops’ Bible, the Geneva, or even the Great Bible, well into the 1630s and 40s. It all depended on whether presiding bishops were keen on the idea.

So who knows what happened in Jamestown? That’s a story waiting to be told, if we can ever find out enough to tell it! For now, we’ll remember the King James Bible John Alden brought over on the Mayflower, which is now on display in the Great Hall at the Folger, and which after January will return to its permanent home at Pilgrim Hall in Plymouth.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Manifold Greatness at Rhodes College

L to R: Naomi Tadmor, Vincent Wimbush, Hannibal Hamlin, Ena Heller, Robert Alter. Notice the Manifold Greatness panel at left!

I just got back from Memphis and the fabulous 1611 Symposium organized by Scott Newstok at Rhodes College. A professor of English at Rhodes, Scott organizes the annual “Shakespeare at Rhodes” Symposium. This year, Scott decided to capitalize on the KJV anniversary by combining several events into one. The symposium itself brought together five international scholars to talk about different aspects of the King James Bible and its rich history: Brian Cummings (Sussex), “In the Literal Sense: The Protestant Bible and the Theory of Reading”; Naomi Tadmor (Lancaster) “The Social Universe of the King James Bible”; Ena Heller (Museum of Biblical Art, New York), “Against the King’s Wishes: Art and the King James Bible”; Vincent Wimbush (Claremont Graduate School), “White Men’s Magic: The Black Atlantic Reads King James”; and me (Ohio State), “Reflections after 2011: What I’ve Learned about the King James Bible.” The distinguished literary critic, biblical scholar, and Bible translator Robert Alter (Berkeley) was the respondent, and he also delivered the Naseeb Shaheen Memorial Lecture, “The King James Bible and the Question of Eloquence,” at The University of Memphis the previous evening. Many audience members attended both events, and they also had the opportunity to see the panel exhibition of Manifold Greatness, which had arrived at Rhodes earlier in the week.

The Manifold Greatness panels were displayed brilliantly, fanning across a beautiful sunlit room in Rhodes’s stunning Barret Library. Hats off to the librarians, and to Scott, for this location! The exhibition, supplemented with some early English Bibles from the Barret collection, was officially opened Friday morning, with remarks by Scott, some brief background on Manifold Greatness by me, and a lovely reception. The guests included a who’s-who of Memphis, from scholars and teachers at Rhodes, U. Memphis, and other local colleges and seminaries, to the Director of Opera Memphis, board members of the Tennessee Shakespeare Company, and other civic, religious, and cultural leaders. I really had the sense that the whole Memphis community was coming together for these several days.

Robert Alter’s lecture was brilliant, delving into aspects of the KJV style and the work of its translators in a way few others could. How many scholars can legitimately speak of the KJV translators as colleagues? The symposium was a rich and exciting exchange of ideas. Brian Cummings wasn’t able to come due to a family emergency, but his intriguing paper was read by Rhodes professor Michael Leslie. The packed audience was diverse, bringing together students and faculty from several institutions, as well as members of the community.

Even after five papers and a formal response, the audience was keen, asking an array of questions for another couple of hours. At several points, we broke for refreshments, and the discussion simply spilled out into the reception area. Conversation continued among all the presenters and several faculty members at a dinner kindly hosted by Scott at his home.

The next day, we had a VIP tour of Elvis’s home Graceland, our special status owing to the Folger’s borrowing of Elvis’s Bible for the Manifold Greatness exhibition. I actually saw the Folger exhibition announced on a videoscreen in the Graceland lobby. And the gentleman who took us on the tour also knew about the Rhodes conference from an article in the local newspaper. We had lunch at the “world-famous” Gus’s Fried Chicken, and there was a “1611 Symposium” poster on the wall. Memphis definitely did Manifold Greatness proud!!

The Manifold Greatness traveling panel exhibition is on display at Barret Library at Rhodes College in Memphis through December 21.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Martin Luther King and the King James Bible

Tomorrow (August 28) was to have been the day for officially opening the new and long-awaited Martin Luther King Memorial in Washington, DC. Hurricane Irene delayed these plans along with so much else. (Check the Memorial’s website for updates on the ceremony plans for the future.) August 28 remains, of course, the anniversary of King’s famous “I have a dream” speech from the March on Washington on August 28, 1963.

For the past week, the site on the Tidal Basin, on a direct line between the Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials, has been open to visitors, though, who could view the impressive sculpture by Lei Yixin and the many quotations from King’s speeches and writings engraved around the site. The Memorial has generated some controversy, first for the choice of a Chinese sculptor. It’s also been pointed out that one of the engraved quotations is broadly paraphrased rather than quoted exactly, and another, though spoken by King, was originally from a sermon given a century earlier by Theodore Parker.

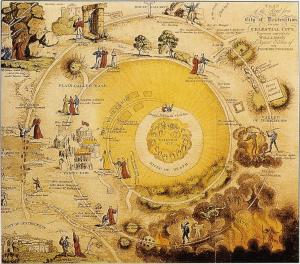

Be all that as it may, the sculpture, “The Stone of Hope,” looks impressive, though I’ve as yet seen it only in photos. The concept derives from a line in King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered 48 years ago tomorrow, from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. King said that with faith in the dream, “we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.” Yixin has shown King himself as a kind of stone of hope emerging out of the marble block. King’s language here, as so often, is deeply biblical. My uncle, Carl Scovel, a Unitarian minister, attended the March on Washington in 1963 and heard King and others speak. He said to me it was striking how biblical King’s rhetoric sounded, far more so than any of the other speakers. Hewing stone comes up a lot in the King James Bible. King may not be thinking of any particular passage, but there are several that he might have had in mind. Moses is commanded by God to hew two tables of stone that will become the Ten Commandments (Exodus 34:1-4), for instance. And Jesus is buried in a tomb hewn out of the rock, with a stone rolled in front of it (Matthew 27:59-60). The Temple in Jerusalem is built by the workers of David and Solomon hewing stones out of the mountain (1 Chronicles 22, 2 Chronicles 2).

One of the inscriptions on the walls of MLK memorial contains a passage from the prophet Amos that obviously spoke to King: he used it often, including during the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott, and later in the “I Have Dream” speech. The wording on the memorial is from the Montgomery speech: “We are determined here in Montgomery to work and fight until justice runs ‘down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream.'” In 1963, King modified the words slightly: “No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until ‘justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.'” The quoted verse is from Amos 5:24 and the language is that of the KJV, with the single exception of the word “justice.” The KJV translators chose “judgment” instead, but the word was altered to “justice” in the American Standard Version (1901), which King may have been remembering as well. (He could also have known the Revised Standard Version of 1952, which also has “justice,” but it changes “mighty stream” to “ever-flowing stream,” so King wasn’t remembering this translation.)

The language of the King James Bible, its word choices, its rhythms and patterns of speech, have been a part of American public oratory for the country’s entire history, especially, though not exclusively, among African Americans. (Lincoln’s speeches were highly biblical.) Appropriately, at the inauguration of American’s first African American president, Barack Obama, the Rev. Joseph Lowry repeated the verse from Amos’s prophecy that was so important to Martin Luther King. In his benediction, Lowry looked forward, as King had done, to the time “when justice will roll down like waters and righteousness as a mighty stream.” That final time of Justice might not yet have arrived, but Lowry must have been thinking that at least some of those waters had rolled down since 1963. King had looked down the Mall toward the Capitol as he shared his dream of racial equality, but Lowry, and Obama, looked back the opposite way from the steps of the Capitol itself.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

The King James Bible and the U.S. Civil War

Drummer boy, Manassas 150th anniversary, July 2011. Copyright Jeff Mauritzen and Discover Prince William & Manassas, VA.

Yesterday, July 21, was the 150th anniversary of the First Battle of Manassas or Bull Run, the first major land battle of the Civil War. The coincidence of the anniversaries of the U.S. Civil War and the publication of the King James Bible offers an opportunity to reflect on how important the KJB was for this crisis in American history.

For both sides, South and North, the war was conceived in biblical terms. As Abraham Lincoln put it in his Second Inaugural Address on March 24, 1865, “Both [North and South] read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.” In the mid nineteenth century, the King James Bible was overwhelmingly the Bible of American Protestant Christians, with the American Bible Society alone publishing a million KJBs annually. Lincoln was sworn in on a copy of the KJB, just as George Washington and other presidents were before him. The key issue in the Civil War was slavery, and for Southerners the Bible provided its justification, as argued in works like Josiah Priest’s Bible Defense of Slavery (Glasgow, KY, 1852). Yet Northern Abolitionists from John Brown to Frederick Douglass (as discussed in this earlier post) found their justification in the Bible too.

In fact, though the KJB, along with Christianity, was introduced to slaves by their owners in hopes it would encourage obedience, the slaves turned the religion and the book against their masters, finding in them instead a source of hope and a manifesto for freedom from bondage. The spiritual “Go Down Moses,” for instance, interprets the story of Israel’s Exodus out of Egypt as a promise for the exodus of blacks out of slavery. The language of African American religion, music, literature, and public oratory has been steeped in the rhythms and phrases of the KJB ever since.

In fact, though the KJB, along with Christianity, was introduced to slaves by their owners in hopes it would encourage obedience, the slaves turned the religion and the book against their masters, finding in them instead a source of hope and a manifesto for freedom from bondage. The spiritual “Go Down Moses,” for instance, interprets the story of Israel’s Exodus out of Egypt as a promise for the exodus of blacks out of slavery. The language of African American religion, music, literature, and public oratory has been steeped in the rhythms and phrases of the KJB ever since.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Gregory Peck Moby Dick Released Today – 1956

On June 27, 1956, the film of Moby Dick was released. Directed by John Huston and starring Gregory Peck and Richard Basehart as Ahab and Ishmael, the film was released by Warner Brothers Studios. The screenplay, more faithful to Melville’s novel than other early film versions, was co-written by Huston and sci-fi author Ray Bradbury. At around the same time, Orson Welles had been thinking of making his own film of Moby Dick, but he gave up the plan on hearing about his friend John Huston’s project. In recompense, Huston gave Welles the memorable part of Father Mapple. From his ship-shaped Nantuckett pulpit, Mapple gives a powerful sermon on Jonah, the biblical book so important to the story of Moby Dick.

On June 27, 1956, the film of Moby Dick was released. Directed by John Huston and starring Gregory Peck and Richard Basehart as Ahab and Ishmael, the film was released by Warner Brothers Studios. The screenplay, more faithful to Melville’s novel than other early film versions, was co-written by Huston and sci-fi author Ray Bradbury. At around the same time, Orson Welles had been thinking of making his own film of Moby Dick, but he gave up the plan on hearing about his friend John Huston’s project. In recompense, Huston gave Welles the memorable part of Father Mapple. From his ship-shaped Nantuckett pulpit, Mapple gives a powerful sermon on Jonah, the biblical book so important to the story of Moby Dick.

“Shipmates, this book, containing only four chapters–four yarns–is one of the smallest strands in the mighty cable of the Scriptures. Yet what depths of the soul does Jonah’s deep sea-line sound! what a poignant lesson to us is this prophet! What a noble thing is that canticle in the fish’s belly! How billow-like and boisterously grand! We feel the floods surging over us; we sound with him to the kelpy bottom of the waters; sea-weed and all the slime of the sea is about us! But what is this lesson that the book of Jonah teaches? Shipmates, it is a two-handed lesson; a lesson to us all as sinful men, and a lesson to me as a pilot of the living God.”

For more on the influence of the King James Bible on Moby Dick, see “Literary Influences” on the Manifold Greatness website.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Ohio State Conference

Well, I should have posted this a couple of weeks ago, but conference organizing takes its toll apparently. I came down with a cold a few days before our conference at Ohio State (May 5-7) and I’ve been struggling with it ever since.

Well, I should have posted this a couple of weeks ago, but conference organizing takes its toll apparently. I came down with a cold a few days before our conference at Ohio State (May 5-7) and I’ve been struggling with it ever since.

The conference, The King James Bible and its Cultural Afterlife, was a great success, though, and all the participants I’ve heard from (we had about 150) enjoyed themselves and the lively exchange of ideas. We had eminent literary scholars from across the world: New Zealand, Belgium, Taiwan, England, Scotland, and across the United States. Universities represented included Oxford, Glasgow, Leuven, Victoria University of Wellington (New Zealand), Yale, Georgetown, William and Mary, Maryland, Purdue, Rutgers, and many more. David Norton (author of The King James Bible: A Short History from Tyndale to Today) gave the keynote address, which focused on biblical language and allusions in Jane Eyre. The plenary panels offered superb papers by scholars of the Reformation, African American literature, English Romanticism, Milton, Gay and Lesbian Studies, and biblical scholarship. Many of the presenters–Stephen Prickett, Jason Rosenblatt, Adam Potkay, Gergely Juhasz, Katherine Bassard, Heather Walton, Michael Wheeler–were contibutors to The King James Bible after 400 Years, but they were joined by Gordon Campbell (Bible: The Story of the King James Bible, 1611-2011), David Jasper (The Sacred Body: Asceticism in Literature, Religion, Art, and Culture), Leland Ryken (The Legacy of the King James Bible), and many others. These books were on display outside the conference theater, along with the book for the Folger-Bodleian exhibitions, Manifold Greatness, a copy sent to us hot off the press.

Another feature of the conference was a reading and talk by Pulitzer Prize winning author, Edward P. Jones. He read passages from his novel The Known World as well as his short story collections about characters in Washington, DC, all chosen to highlight the influence of the King James Bible. He spoke afterward of how the minimalism of the Old Testament narrative had shaped his own style, avoiding unnecessary adjectives and adverbs and minimizing authorial intrusions.

Another feature of the conference was a reading and talk by Pulitzer Prize winning author, Edward P. Jones. He read passages from his novel The Known World as well as his short story collections about characters in Washington, DC, all chosen to highlight the influence of the King James Bible. He spoke afterward of how the minimalism of the Old Testament narrative had shaped his own style, avoiding unnecessary adjectives and adverbs and minimizing authorial intrusions.

Not only was the discussion outstanding over the several days, but the weather weirdly cooperated with us, giving us the only sunshine Columbus had seen for many weeks.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.