Charles Jennens. Messiah. An oratorio. London, 1749? Folger Shakespeare Library.

On April 13, 1742, a new oratorio by the famous composer George Frideric Handel made its debut in Dublin, Ireland.

The performance was held to benefit three local charities: prisoners’ debt relief, the Mercer’s Hospital, and the Charitable Infirmary. The Dublin News-Letter provided an early critique on the work, praising the oratorio as “…far surpass[ing] anything of that Nature which has been performed in this or any other Kingdom”.

Handel’s Messiah has continued to be performed ever since. Its librettist, Charles Jennens, drew from the King James Bible for his text, with one exception: lines from the psalms are taken from Miles Coverdale’s earlier translations in the Book of Common Prayer.

To hear excerpts from Messiah, with information on their KJB connections, please enjoy the Handel’s Messiah interactive feature on the Manifold Greatness website. More information on Handel himself appears in this previous post.

Amy Arden assisted in the development and production of the Manifold Greatness website. She is a communications associate at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

April 13, 2012 | Categories: At the Folger, Influences, The KJB in History, The KJB Today | Tags: anniversary, Authorized King James Version, Book of Common Prayer, Charles Jennens, choral music, Christmas, community, Dublin, Easter, George Frideric Handel, Handel, holiday, Ireland, King James Bible, Messiah, Miles Coverdale, oratorio, Psalms, sing-along | Leave a comment

Trevelyon Miscellany. 1608. Folger.

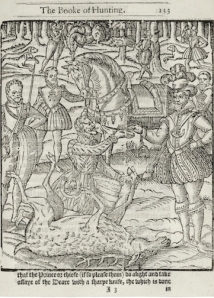

OK, more myths to bust. King James I did not translate the King James Bible, and he was also no saint! I’ve seen at least one recent book (a collection of KJV excerpts) entitled King James’s Bible. The implicit claim of this title is true, to the extent that the KJV was commissioned by King James, and it was presumably the Bible he himself used from 1611 until his death in 1625. But, in this last sense, it was pretty much everybody else’s Bible, too.

James certainly did not do any of the translating of the KJV. He was a very scholarly king, interested in theology and the Bible. Among other works, he wrote a book on demonology (1597) and a learned exposition on several chapters of Revelation. He also translated some of the Psalms into meter, but this practice tended to involve turning English prose versions into verse, rather than rendering the original Hebrew into English. Lots of people wrote metrical Psalms at this period, and most didn’t know Hebrew.

James set the KJV ball rolling, but once it was in motion he more or less left it alone. The eminent scholars worked away on the project for years, without any involvement from the monarch. The dedicatory Epistle to King James at the front of the KJV refers to the king as the “principle mover and author of this work.” However, the word “author” in this case doesn’t mean what it does in a phrase like “the author of Shakespeare’s works is William Shakespeare.” It’s closer to our word “authority,” or really someone who authorizes or instigates (as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it).

James I at the hunt (standing, right). Gascoigne, The noble art of venerie or hunting. 1611. Folger.

It’s interesting that the British tend to refer to the KJV as the “Authorized Version,” while Americans prefer the “King James Bible.” The term “Authorized Version” dates from only the nineteenth century, while as early as 1723, according to one writer, it was “commonly called King James’s Bible.” In the seventeenth century, most people just referred to it as the new or latest translation. For the first American edition of the KJV, the “Revolutionary Bible” of 1782, the printer Robert Aitken carefully removed any reference to King James.

I’ve also occasionally heard the KJV described as the “St. James Bible.” Maybe people have the “St. James Infirmary Blues” going through their heads, or they’re thinking of the many churches dedicated to St. James (there are actually several saints by this name, including St. James the Great, St. James the Less, and St. James the Just). I don’t know. But the only James associated with the KJV is King James I, and he was never canonized. Not only was he less than saintly in his behavior (a bit of a party animal), but he was not a Catholic, which seems a fairly basic requirement for sainthood.

We can keep calling it the King James Bible, but we shouldn’t let that nickname mislead us into giving James more credit than he’s due.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library, on view through January 16, 2012.

December 28, 2011 | Categories: From the Curators, The KJB in History | Tags: Authorized Version, demonology, King James Bible, King James I, Psalms | 1 Comment

There is more to books than just the texts they contain. Books are historical artifacts whose physical makeup and features tell us something about the people who owned them and the cultures that produced them. In this way, each book has its own story to tell.

While searching for books to use in our Manifold Greatness exhibition, I came across a copy of The third part of the Bible with the following inscription: “This was ye [the] only booke I carried in my pockett when I travelld beyond ye [the] seas ye [the] 22d year of my Age; & many years after Just. Isha[m].”

I was astonished. While many book owners from the early modern period inscribed their names into their books and perhaps even supplied a date, very few provided such personal details. We not only know who owned this book but where he kept it and where he took it. While it is taken for granted that small books often traveled in the pockets of their owners, it is wonderful to have confirmation from a contemporary owner.

Identifying “Just. Isha[m]” turned out to be a surprisingly easy task. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (DNB) brought me to Sir Justinian Isham (1611–1675), second baronet of Lamport Hall, Northamptonshire. The DNB entry states that Isham traveled to the Netherlands in 1633 at the age of twenty-two, a perfect match to the book’s inscription, “beyond ye seas ye 22d year of my Age.”[1]

When I showed Isham’s Bible to Heather Wolfe, the Folger’s Curator of Manuscripts, she recalled that two scholars, Elizabeth Clarke and Erica Longfellow, had transcribed the diary of a woman from the same period named Elizabeth Isham and wondered if she could be related to Justinian. Looking at the diary online I found entries from 1633 that confirm that she was his sister. She writes, “‘my B[rother] went beyond sea” and later “my B[rother] came from beioynd [sic] sea.”[2]

Also through the diary I learned of the Isham family’s close relationship with the Stuteville family. In the back of Isham’s Bible is a manuscript IOU contract between sisters Susan and Elizabeth Stuteville.

Another interesting feature of the book is the manuscript index to the Psalms found in the book’s blank endpapers. Here Isham records the numbers of particular psalms appropriate for particular occasions: morning, evening, mercy, sickness, joy, communion, and comforts. The Psalms section of the book is also where he wrote the most manuscript notes.

I continue to be amazed by the amount of history contained in this one, small book. It really is one of the treasures of the Folger. I must admit it’s my favorite book in the exhibition.

Steven Galbraith, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Books, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

[1] R. Priestley, ‘Isham, Sir Justinian, second baronet (1611–1675)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/14489, accessed 13 April 2010]

[2] Elizabeth Clarke and Erica Longfellow, “Constructing Elizabeth Isham,” University of Warwick, Centre for the Study of the Renaissance, 28 Jan 2009 [http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/ren/projects/isham/, accessed 5 May 2010]

August 23, 2011 | Categories: At the Folger, From the Curators | Tags: Elizabeth Isham, Lamport Hall, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Psalms, Sir Justinian Isham, University of Warwick | 1 Comment

Messiah, by Tafelmusik, Toronto. Photo by Gary Beechey.

On April 13, 1742, a new oratorio by the famous composer George Frideric Handel debuted in a music hall in Dublin, Ireland. Handel’s Messiah has continued to be performed ever since, a perennially popular work that offers many concertgoers their most regular, and likely their most full-throated, exposure to the text of the King James Bible. Its librettist, Charles Jennens, assembled most of the words from the KJB, with one exception: lines from the psalms are taken from Miles Coverdale’s earlier translations in the Book of Common Prayer.

In celebration of April 13, we’ve assembled a new “Handel and the KJB” Flickr slideshow that combines a rare early surviving “word book” of Handel’s Messiah from the Folger Shakespeare Library with a look at modern sing-along holiday performances of the work, a tradition in many churches and communities. To hear excerpts from Messiah, with information on their KJB connections, please enjoy the Handel’s Messiah interactive feature on our brand-new Manifold Greatness website.

And yes, the premiere really was April 13. We even found this marker!

April 13, 2011 | Categories: At the Folger, Influences, The KJB in History, The KJB Today | Tags: anniversary, Authorized King James Version, Book of Common Prayer, Charles Jennens, choral music, Christmas, community, Dublin, Easter, George Frideric Handel, Handel, holiday, Ireland, King James Bible, Messiah, Miles Coverdale, oratorio, Psalms, sing-along | 1 Comment