King James, seen here in our online coloring activity, did not translate the King James Bible. It also wasn’t published on May 2.

It’s May 2 today, and that makes it the anniversary of… a classic May 2, 2011, blog post by Manifold Greatness co-curator Hannibal Hamlin, explaining just why May 2 isn’t and couldn’t be the anniversary of the King James Bible’s publication date.

But the curious tradition of May 2 is not the only King James Bible myth that he’s discussed on this blog. One of our all-time most popular blog posts (with a fairly self-explanatory title, we think) remains Shakespeare did not write the King James Bible, no way, no how. Nor did the King James Bible influence Shakespeare’s plays: the timing was wrong, as explained here.

Dealing with another common misconception, King James didn’t write the King James Bible, either. See this blog post for that explanation.

Curious to learn more? These and other questions are included as Myth or Reality? FAQS on our Manifold Greatness website, too. What makes the King James Bible so subject to myths, stories, and misconceptions? Perhaps, in part, it’s just a sign of its cultural and religious importance. As for May 2, it’s an unusually prosaic “myth” about a book publication date, rarely the stuff of legend or romance. As Hannibal Hamlin suggests in his original “May 2” blog post, perhaps just having a definite date—any date—helps satisfy our perennial desire for certainty.

The Manifold Greatness project, including this blog, began in 2011, the 400th anniversary year of the 1611 King James Bible. To learn more about the origins, creation, and broad influence of the King James Bible, explore our Manifold Greatness website. To try our coloring game, select “Coloring” from the Games and Activities section of the website’s “Kids Zone.”

May 2, 2013 | Categories: The KJB in History | Tags: coloring, Debunking, King James Bible, King James I, legend, myth, pictures, Shakespeare, Shakespeare's Birthday, tradition | Leave a comment

Library employees Trina Jones and Mack Freeman pose with artist/student worker Jesse Carpenter.

What do you do when you have an exhibit celebrating the 400th anniversary of the printing of the King James Bible? What do you do to get a small, rural community in south Georgia in the right mindset for an exhibit and an onslaught of information on the politics and history surrounding a book that most people know very well, but probably have never thought seriously about? Well, in Tifton, Georgia, we put on a Renaissance Faire and partied like it was 1611!

This event gave a lot of people an opportunity to get in touch with their inner RenRat. Attendees were encouraged to attend in costume and were given handouts instructing them on how to speak “The King’s English.” The library staff and our amazing volunteers lavished endless attention on costumes and pavilions. Jesse Carpenter, one of our student workers, was recruited to produce cutouts that included King James himself. Members of the Literacy Volunteers and the Rotary Club were cajoled into selling era-appropriate food to our visitors. One of the interesting facts we discovered while researching the time is that gingerbread men were invented during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I!

A children’s tent was dedicated to the production of quill pens, swords, shields, and crowns. It is hard to know how long the street will be glittered. We also had a volunteer that taught a steady stream of people how to play Nine Man Morris, a game that we discovered was popular during the time. Wagering on outcomes was not encouraged during our faire.

One of the highlights of the faire was the participation of the Society for Creative Anachronism. These talented individuals came and set up tents and demonstrated blacksmithing, illumination, dancing, sewing techniques, and FIGHTING! Knights fought for the honor of fair maidens picked from the audience and to advance their status in their shires. It was loud and exciting and very, very popular with our visitors. Cameras were encouraged and the fighters were probably the most photographed characters on Faire day.

Costumed volunteers added ambiance to our Manifold Greatness opening day!

Why did we open the exhibit this way? It was important for us to have a strong kickoff event for the exhibit. We were looking for something that would appeal to a large number of people, people who might not have thought to come to the exhibit, but might come to the Faire, eat a smoked turkey leg, and then decide to go and see what was happening with the exhibit. We believe that the Faire did this for us. The exhibit had a very strong opening day and we hope that, because we were able to promote the rest of the programming surrounding the exhibit more personally with the Faire-goers, we have good turnouts for what is to come.

Vickie Horst is the Manager of Tifton-Tift County Public Library in Tifton, Georgia.

April 26, 2013 | Categories: On Tour | Tags: armor, crafts, Elizabeth I, King James Bible, King James I, Nine Man Morris, Renaissance, Renaissance Faire, Society for Creative Anachronism | 3 Comments

Triangle Scottish Dancers at Cameron Village Regional Library exhibit opening, North Carolina

History of the harp

Because North Carolina has a strong Scottish heritage, we decided to highlight King James’s own Scottish heritage in our Manifold Greatness opening celebration at Cameron Village Regional Library in Raleigh, North Carolina.

The afternoon began with a performance of highland dancing by the Triangle Scottish Dancers, a local group that is part of the Scottish Cultural Organization of the Triangle (SCOT). Highland dancing differs from country dancing in that the latter is performed by couples who walk around each other in patterns, much like American square dancing. Highland dancing, in contrast, is performed by individuals and involves very intricate footwork. It is similar to the Irish dancing that was popularized by the “Lord of the Dance”.

Harpist Anita Burroughs-Price with interested observers

Most highland dance groups are made up of girls and young women, as is the case with our group. More than one attendee remarked on how nice it was to see a group of girls performing together in such an accomplished way. Even the bagpipe player is a teenage girl.

After the dance performance in the atrium, the piper played while the dancers led the crowd upstairs to the exhibit room. There refreshments were served while North Carolina Symphony harpist Anita Burroughs–Price performed music from the Jacobean era, and told attendees about the history of the harp from its beginning as an outgrowth of the hunter’s bow to the modern harp we know today.

George Birrell of SCOT

During the harpist’s break, SCOT member George Birrell gave a talk about kilts and read some Scottish poetry. George and Anita then collaborated on an impromptu duet, Anita playing the harp while George recited the words to “Auld Lang Syne,” a Scottish song with words by the poet Robert Burns. An earlier version of the song has been attributed to Sir John Ayton, a scholarly advisor to King James.

Eventually, the afternoon of music, food, and dance drew to a close. One of the comments left on the white board in the exhibit room summed it up: “Great display. Absolutely spiffing!”

Sue Scott is Arts and Literature Librarian at Cameron Village Regional Library, Raleigh, North Carolina.

March 15, 2013 | Categories: Kids & Families, On Tour, The KJB in History | Tags: Anita Burroughs-Price, harp, King James Bible, King James I, King James VI, Music of Scotland, North Carolina Symphony, Robert Burns, SCOT, Scottish Cultural Organization of the Triangle, Scottish highland dance, Triangle Scottish Dancers | Leave a comment

Trevelyon Miscellany. 1608. Folger.

OK, more myths to bust. King James I did not translate the King James Bible, and he was also no saint! I’ve seen at least one recent book (a collection of KJV excerpts) entitled King James’s Bible. The implicit claim of this title is true, to the extent that the KJV was commissioned by King James, and it was presumably the Bible he himself used from 1611 until his death in 1625. But, in this last sense, it was pretty much everybody else’s Bible, too.

James certainly did not do any of the translating of the KJV. He was a very scholarly king, interested in theology and the Bible. Among other works, he wrote a book on demonology (1597) and a learned exposition on several chapters of Revelation. He also translated some of the Psalms into meter, but this practice tended to involve turning English prose versions into verse, rather than rendering the original Hebrew into English. Lots of people wrote metrical Psalms at this period, and most didn’t know Hebrew.

James set the KJV ball rolling, but once it was in motion he more or less left it alone. The eminent scholars worked away on the project for years, without any involvement from the monarch. The dedicatory Epistle to King James at the front of the KJV refers to the king as the “principle mover and author of this work.” However, the word “author” in this case doesn’t mean what it does in a phrase like “the author of Shakespeare’s works is William Shakespeare.” It’s closer to our word “authority,” or really someone who authorizes or instigates (as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it).

James I at the hunt (standing, right). Gascoigne, The noble art of venerie or hunting. 1611. Folger.

It’s interesting that the British tend to refer to the KJV as the “Authorized Version,” while Americans prefer the “King James Bible.” The term “Authorized Version” dates from only the nineteenth century, while as early as 1723, according to one writer, it was “commonly called King James’s Bible.” In the seventeenth century, most people just referred to it as the new or latest translation. For the first American edition of the KJV, the “Revolutionary Bible” of 1782, the printer Robert Aitken carefully removed any reference to King James.

I’ve also occasionally heard the KJV described as the “St. James Bible.” Maybe people have the “St. James Infirmary Blues” going through their heads, or they’re thinking of the many churches dedicated to St. James (there are actually several saints by this name, including St. James the Great, St. James the Less, and St. James the Just). I don’t know. But the only James associated with the KJV is King James I, and he was never canonized. Not only was he less than saintly in his behavior (a bit of a party animal), but he was not a Catholic, which seems a fairly basic requirement for sainthood.

We can keep calling it the King James Bible, but we shouldn’t let that nickname mislead us into giving James more credit than he’s due.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library, on view through January 16, 2012.

December 28, 2011 | Categories: From the Curators, The KJB in History | Tags: Authorized Version, demonology, King James Bible, King James I, Psalms | 1 Comment

James I. Miniature, ca. 1620. Folger.

Happy Birthday King James! James I of England, whose birthday is this Sunday, June 19, is the “King James” of the King James Bible. He became King James VI of Scotland at the age of one in 1567, after his mother, Mary (Queen of Scots) was forced to abdicate. Mary was implicated in the death of her second husband (and cousin), Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, James’s father. As retold in novels, plays, opera, and films, Mary herself was imprisoned, and eventually beheaded, by her cousin (once removed), Elizabeth I of England. When Elizabeth died in 1603, James inherited her throne. One weirdness in this succession is that James inherited the crown from the queen who executed his mother, but since Mary was likely involved in the murder of his father, he probably had mixed feelings about her death.

When James came down from Scotland, his new English subjects were naturally concerned about their new king’s religious views and the future of church organization and worship in England. To settle matters, James convened a conference in January of 1604 at the palace of Hampton Court. Though it was not on the agenda, the project for a new translation of the Bible originated in these discussions.

Despite popular misconceptions, James himself had little to do with the translation, apart from setting it in motion,and providing it with royal sanction. (The translators prominently dedicated it to him, too.) He was a learned monarch, deeply engaged with theological questions, and he wrote a number of metrical versions of Psalms. But his learning was not up to the level of the translators.

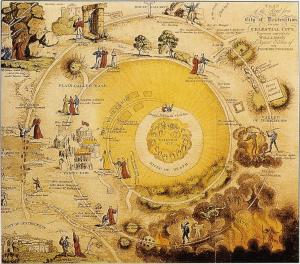

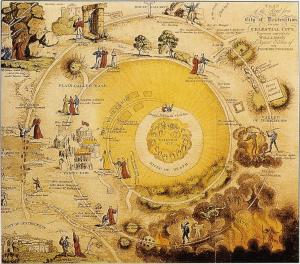

Map of Christian's journey from Pilgrim's Progress

His one area of contribution to the translation was in shaping the guiding principles for the translators (written by Archbishop Richard Bancroft), especially in the decision to avoid marginal interpretative notes. Such notes had been a popular feature of the Geneva Bible, but a number of these, written by Protestant exiles during the reign of Queen Mary, were sharply critical of monarchs. The King James Bible, as it came to be known, was to be free of such a radical taint. Little did James know that the Bible he sponsored would become the Bible of the radicals John Milton, John Bunyan (author of Pilgrim’s Progress, right), and William Blake, as well as of America, the British colonies that threw off their king to become a democratic republic.

Hannibal Hamlin, associate professor of English at The Ohio State University, is co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

June 18, 2011 | Categories: From the Curators, Influences, The KJB in History | Tags: American colonies, Authorized King James Version, birthday, Elizabeth I, England, Folger Shakespeare Library, Geneva Bible, Hampton Court, John Bunyan, John Milton, King James Bible, King James I, Mary I, Mary Queen of Scots, Scotland, William Blake | Leave a comment

‘Manifold Greatness: Oxford and the Making of the King James Bible‘ opened, appropriately enough, on Good Friday, April 22, and welcomed nearly a thousand visitors across the Easter weekend. The week before the opening was in many ways revelatory, as the books were arranged in the cases, the loaned items arrived, and the panels were set in place. It was inspiring to see the exhibition taking shape before our eyes, as real books took the place of sketches, and the ‘conversation’ that we had envisaged between the different items in each case began to take shape. It was also humbling: this exhibition is the first time that some of these books have been reunited in one room since they were used by the King James translators.

It was remarkable to see the panel designs becoming a physical reality. The team has for the first time used banners as part of the room design for this exhibition: two huge banners hung at opposite ends of one wall feature the Old and New Testament title pages of the 1611 King James Bible.

Between them is a portrait of King James, which is itself framed by two banners carrying verses from 1611: one from the Old Testament, as translated by the First Oxford Company (Isaiah 49:13) and one from the New Testament, as translated by the Second Oxford Company (Revelation 19:6). For these banners I chose verses that not only resonate poetically, but that also address one of the key themes of the exhibition – the many voices of the King James Bible.

Written by committees, the KJB re-uses many words and phrases from earlier translations, and its own words were adapted in poetry and fiction by the later writers such as George Herbert, John Milton and Daniel Defoe who feature in our exhibition. So these two verses from Isaiah and Revelation capture for me not only the majestic, collective voice of heavenly rejoicing, but also this idea of the many voices involved in Bible translation and reception:

Portrait of King James I, Bodleian.

Sing, O heaven, and be joyfull, O earth, and breake forth into singing, O mountaines: for God hath comforted his people, and will have mercy upon his afflicted. (Isaiah 49:13)

And I heard as it were the voice of a great multitude, and as the voice of many waters, and as the voice of mightie thundrings, saying, Alleluia: for the Lord God omnipotent reigneth. (Revelation 19:6)

Helen Moore chairs the curatorial committee of the Bodleian ‘Manifold Greatness’ exhibition. She is Fellow and Tutor in English at Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

May 5, 2011 | Categories: At the Bodleian, From the Curators, The KJB in History | Tags: banners, Bodleian Library, First Oxford Company, King James Bible, King James I, Second Oxford Company | Leave a comment